“Give us this day our daily bread.”

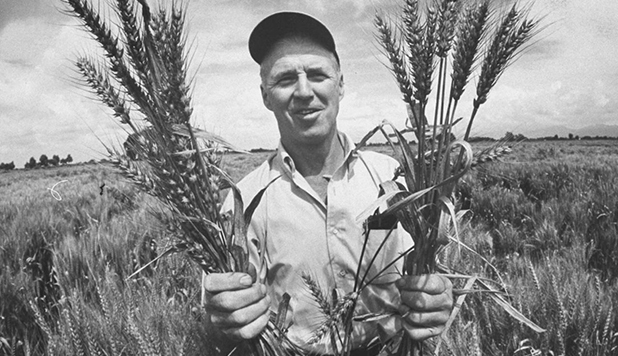

When I hear this passage from The Lord’s Prayer I am reminded of a more earthly being for whom I once worked — Norman Borlaug. Had Borlaug lived past his 95th year, he would turn 100 on March 25th which appropriately also happens to be National Agriculture Day. Borlaug’s 100th is being commemorated with the unveiling of a statue of him in the Iowa section of Statuary Hall at our nation’s capitol.

It is a fitting tribute to a man who more than any other human is responsible for providing daily bread for billions of people, untold millions of whom many believe would have perished for lack of food were it not for his efforts. As many in the world of agriculture know, Borlaug was working on a Rockefeller Foundation grant as a wheat breeder in Mexico in the 1940s when he decided to defy conventional scientific wisdom and pursue a course of action that his “farm savvy” told him would work but which conventional scientific wisdom said would not.

Always in a hurry, Borlaug was frustrated by the slow progress he was making in coming up with improved spring wheat varieties. It grated on him that after harvesting his experimental plots each year, he had to wait until the next growing season to plant new ones. He realized Mexico, with its variety of latitudes and elevations actually had two growing seasons. So Borlaug proposed that as soon as he harvested his plots in the central highlands he would proceed to the Yaqui valley in Sonora to plant again. His fellow scientists said it would not work because it was thought that seeds needed a resting period after harvest if they were to regain their productivity for the coming year. And besides, Sonora had a different set of growing conditions than the highlands which would exert different pressures on the experimental plots.

Nevertheless, Borlaug persisted in his proposal and when his boss refused permission to carry it out, he resigned. After some third party intervention, cooler heads prevailed and Borlaug embarked on a program that came to be known as shuttle breeding. By the middle 1940s Borlaug was breeding wheat at a whirlwind rate compared to others in his profession. He did it in two locations that were separated by 700 miles on the map and 8,500 feet in elevation.

It turned out that shuttle breeding had none of the disadvantages the scientific community believed it would. The seeds didn’t need any more rest than this Iowa farm boy-turned-wheat breeder did. In fact, there were advantages beyond the doubling of the breeding cycle. The new wheats turned out not to have problems with day length. Normally, wheat varieties have difficulty adapting to radically different environments due to changing day length. But Borlaug planted in the North when the days were getting shorter, at low elevation and higher temperatures. Then he took the harvested seed south and planted it at high elevation, when days were getting longer and there was plenty of rain. Evidently, the wheat didn’t mind. Before long he had new wheats that fit the whole range of farming conditions across the breadth and length of Mexico even though he was not breeding wheat in all those regions. This was not supposed to happen if you read the scientific literature of the day.

While the new lines of wheat were more productive and less prone to disease, they were still prone to lodging as the heads became heavier with grain and the stems proved unable to support their weight when rain and wind struck as it often does around harvest time. Borlaug solved this problem, known as “lodging”, by crossing his wheat with dwarf varieties from Japan which had short, stiff stems. The result was high yielding disease-resistant wheat that didn’t blow over in a storm. By the 1960s virtually all Mexico’s wheat crop consisted of varieties bred by Borlaug.

This transformation in Mexico’s agricultural productivity came at a time when Asia, particularly India and Pakistan, were facing famine. In 1963, Rockefeller sent Borlaug to India to work on dwarf wheat there. He encountered initial resistance from the bureaucrats but as the famine worsened, he was given the green light. Borlaug and his Indian colleague M.S. Swaminathan saw to it that the wheat was planted. When it was harvested, the yields were the highest ever recorded in that part of the world. India imported thousands of tons of Borlaug-bred wheat for planting and by the early 1970s, India and Pakistan were, like Mexico before them, self-sufficient in wheat. There was so much wheat that it surpassed the transportation and storage capabilities in many areas. Thus was born what came to be known as the Green Revolution and Norman Borlaug was widely recognized as its father. In 1970, Borlaug was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Many more awards followed.

Meanwhile, Borlaug continued his field work but recognized the need for a Nobel laureate such as him to visit the halls of power and impress upon world leaders the need to invest more in agricultural research and to translate that research into practices on the land that will increase productivity. And, he pushed doing it sustainably so that our growing world population can thrive rather than recede into the cycles of feast and famine so common in the past. Among his messages was the fact that high-yield farming reduced deforestation due to slash-and-burn farming.

Over the years, a phalanx of Borlaug detractors developed, primarily from the ranks of environmentalists. They say Borlaug’s discoveries have led to high-input farming, concentration of land ownership in fewer hands, crowding out of subsistence farming and damage to the environment. These criticisms seem unfair to me because even in cases where they are true, they level blame at the scientist for the activities of the business man.

My involvement with Borlaug occurred in 2000 when he and his disciples at the land grant colleges saw the digital revolution as an opportunity to develop an organization that would deliver online learning to stakeholders across the global food and agriculture system. I was recruited to develop the business plan, procure funding and serve as Chief Executive Officer of Norman Borlaug University. I met Borlaug, by then in his middle 80s, at the airport in Des Moines to discuss the project. His first words were “Call me Norm.” I found this difficult to do. When I offered to carry his suitcase he gave me determined look and said “You carry yours and I’ll carry mine.” Only later did I learn that Norm was a college athlete who occupied a position of honor at the NCAA Wrestling Hall of Fame.

As our working relationship grew, I realized that Norm’s approach to the world reminded me of nothing so much as a farmer standing in his field or crawling over a piece of equipment, scratching his head and trying to figure out the solution to a problem. We managed to launch the university thanks to start-up financial support from James Borel who ran DuPont ‘s agricultural enterprise. And we made progress, securing an agreement to provide courses from the land grant colleges in the U.S. and doing some initial course development. The following year, however, the dotcom meltdown was in full swing and additional funding proved difficult to find even when Norm was in the room helping pitch potential funders. In the end, we agreed the venture was ill-timed and ceased operations.

In his later years, Borlaug continued his work to improve crop productivity, primarily working with corn in Africa. At the time of his death at age 95, he had penned a number of opinion pieces in prominent publications urging leaders to fund efforts to find ways to improve crop productivity sustainably. In 2009, the year he died, he warned in The Wall Street Journal that “…it took 10,000 years to attain the production of roughly six billion gross tons of food per year. Today, nearly seven billion people consume that stockpile almost in its entirety every year.” And, he cited an Oxfam study concluding that climate change might reverse 50 years of work to end poverty resulting in, said Oxfam, “the defining human tragedy of this century.” Clearly, we have our work cut out for us.

In 1986, Borlaug founded the World Food Prize, headquartered in his home state of Iowa, to draw attention to the importance of the agricultural sciences. To learn more about the prize and the man, it’s worth visiting their web site by clicking here. You will find an interactive map of Norm’s career and an excellent tribute to him penned by Kenneth Quinn who administers the prize.

—Earl Ainsworth

P.S. Borlaug’s concerns will be addressed by the Society as Duncan Allison and his activities committee are putting together a series of guest speakers for the coming year who will address the issues of increasing food production sustainably.